The Place of No Story: "My Birth" by Carmen Winant

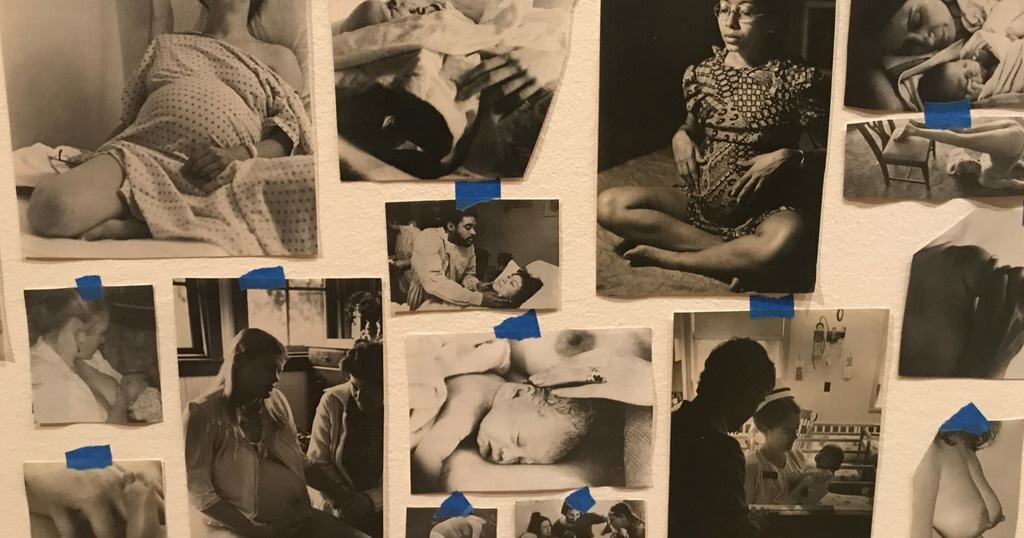

They started popping up in New York City area birth workers’ Instagram feeds in the spring months of this year - cryptic images of a collection of birth photographs taped to a white wall with blue painter’s tape. Some of the images were zoomed in, showing just a few photos; others were zoomed out to reveal an entire wall covered in hundreds of photos of bellies, babies, placentas, breasts… Birth workers’ social media feeds are generally overflowing with birth photography, but this was something different, worth a double take: when do we see birth photographs displayed so casually, so publicly - and in such multiplicity? What are we looking at here?What we are looking at, as it turns out, is artist Carmen Winant’s installation “My Birth,” for the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibit “Being: New Photography 2018.” “My Birth” is composed of over 2000 photographs of people in various phases of the childbearing year, from pregnancy to breastfeeding. Winant collected the images from books, pamphlets, and magazines found in estate sales, garage sales, attics, and so on. She cut the photos out, arranged them in a mosaic, and taped them to the two facing walls of a corridor that connects one gallery room of the “Being” exhibit to another.In person, the effect of the installation is overwhelming. There are so many images packed together that it’s hard to know where - or how - to look. The eye flits back and forth, seeking patterns where there are none. Here a baby at the breast, here a mother grimacing mid-contraction; here a stretched perineum with a crowning occiput, here a smiling pregnancy portrait; here a surgeon’s gloved hands, here a rumpled bed. Some viewers lean, crouch, or stretch to examine individual images; some stand back to take in the whole; some simply toss a quick glance as they walk through the corridor on their way to the next room. (Thus we see the irresistible conceptual pull of birth: every move we make around it takes on symbolic meaning.) In “The Art of Birth,” an essay for Volume 5 of Contemporary Art Review L.A., Winant writes of her search for images of birth in contemporary art (spoiler alert: there aren’t many), and her largely unfulfilled craving to express her own birthing experience and to hear others express theirs. “My Birth” - the installation, as well as the accompanying book by the same name - functions as a response to these empty spaces that Winant encountered, a movement towards addressing the lack of birth images in contemporary art and the lack of birth conversations in the cultural discourse at large. (The book takes a slightly different approach from the installation, juxtaposing a selection of the found images with pictures of Winant’s own mother in childbirth, and interspersing written reflections on Winant’s efforts to understand and articulate the birthing experience. The first few pages and the inside of the dust jacket contain a long catalogue of questions that could be asked about any given birth - “Where did you sense the contractions? Did you dim the lights? Could you open your eyes?”)  Experienced birth professionals - perhaps particularly Birthing From Within professionals, who are trained to tune in to the cyclical inner journeys of parenthood - may not be surprised to learn that “My Birth” is, literally speaking, the project of a new parent. Winant wrote “The Art of Birth,” describing the exploratory stages of the work, when her first baby was only nine weeks old; she completed “My Birth” while pregnant with her second. The project contains recognizable elements of the new parent’s sharp hunger to locate and communicate a coherent story, to catalogue-contextualize-quantify their experience, to tell it and hear it told, to show it and have it seen. (Given that the audience of this blog is largely birth professionals, it’s worth noting here that the new parent’s craving for story is often mirrored in the newly-minted birth professional. Many new birth professionals share the new parent’s enthusiasm for constructing narratives about birth and birthing experiences, collecting details, determining cause and effect, and filling space with questions, answers, information, opinion, and explanation. Indeed, it may be interesting to imagine Winant herself as a new birth professional, a person who has recently embarked upon the professional study of birth.)While the emphasis in “My Birth” on seeing and expressing does in many ways speak to the particular perspective of the new parent (or new birth professional), the work as a whole lands in a deeper, more nuanced place. As we linger with the images on the walls or in the pages of the book, confronted with their simultaneous specificity and universality, coherent story-making begins to slip away. Rather than discovering that this image shows a good birthing practice and that image shows a bad one, or concluding that birth is natural or over-medicalized or joyous or frightening, we find ourselves immersed in the concrete particularities of the birthing body in all of its manifestations - sweat, blood, grimaces, bulges, grins. Each turn of the page, each movement of the eye, reveals yet another image, slightly different from those around it, but also fundamentally the same. Instead of locating a clear narrative, we find potential meanings multiplying into infinity, or compressing themselves into one single image - the image, for example, of a laboring woman pressing her face into the crook of someone’s elbow. In both directions - infinity or singularity - the before and after disappear; interpretation becomes irrelevant.

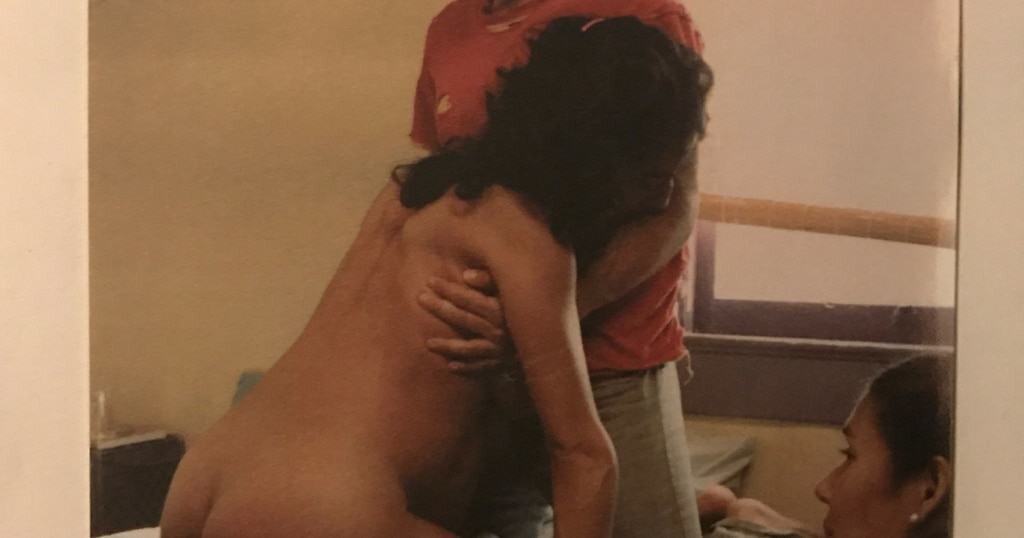

Experienced birth professionals - perhaps particularly Birthing From Within professionals, who are trained to tune in to the cyclical inner journeys of parenthood - may not be surprised to learn that “My Birth” is, literally speaking, the project of a new parent. Winant wrote “The Art of Birth,” describing the exploratory stages of the work, when her first baby was only nine weeks old; she completed “My Birth” while pregnant with her second. The project contains recognizable elements of the new parent’s sharp hunger to locate and communicate a coherent story, to catalogue-contextualize-quantify their experience, to tell it and hear it told, to show it and have it seen. (Given that the audience of this blog is largely birth professionals, it’s worth noting here that the new parent’s craving for story is often mirrored in the newly-minted birth professional. Many new birth professionals share the new parent’s enthusiasm for constructing narratives about birth and birthing experiences, collecting details, determining cause and effect, and filling space with questions, answers, information, opinion, and explanation. Indeed, it may be interesting to imagine Winant herself as a new birth professional, a person who has recently embarked upon the professional study of birth.)While the emphasis in “My Birth” on seeing and expressing does in many ways speak to the particular perspective of the new parent (or new birth professional), the work as a whole lands in a deeper, more nuanced place. As we linger with the images on the walls or in the pages of the book, confronted with their simultaneous specificity and universality, coherent story-making begins to slip away. Rather than discovering that this image shows a good birthing practice and that image shows a bad one, or concluding that birth is natural or over-medicalized or joyous or frightening, we find ourselves immersed in the concrete particularities of the birthing body in all of its manifestations - sweat, blood, grimaces, bulges, grins. Each turn of the page, each movement of the eye, reveals yet another image, slightly different from those around it, but also fundamentally the same. Instead of locating a clear narrative, we find potential meanings multiplying into infinity, or compressing themselves into one single image - the image, for example, of a laboring woman pressing her face into the crook of someone’s elbow. In both directions - infinity or singularity - the before and after disappear; interpretation becomes irrelevant.

Thus we glimpse the place of no-story, the place we reach when our birth experiences are so fully integrated into our Selves that we no longer feel the need to arrange them into directional narratives.

The list of questions in the book could also be understood as emerging from the drive towards story, the new parent’s impulse to (over)ask and (over)share in order to define their own experience. Indeed, in his New Yorker piece on “My Birth,” Philip Gefter quotes Winant as saying that the questions are all ones that she herself would be willing to answer about her own births: “Just ask me.” But the longer one contemplates the questions, the more they, like the images, begin to illuminate the place of no-story: not pointedly demanding details, but instead gently turning the experience this way and that, observing it with tender but dispassionate curiosity.

The list of questions in the book could also be understood as emerging from the drive towards story, the new parent’s impulse to (over)ask and (over)share in order to define their own experience. Indeed, in his New Yorker piece on “My Birth,” Philip Gefter quotes Winant as saying that the questions are all ones that she herself would be willing to answer about her own births: “Just ask me.” But the longer one contemplates the questions, the more they, like the images, begin to illuminate the place of no-story: not pointedly demanding details, but instead gently turning the experience this way and that, observing it with tender but dispassionate curiosity.

“Were you thirsty?” “What sensation did you experience with the cord being cut?” “Did you weep?”

Inside the back cover, hidden by the dust jacket, we discover one final thought: “By the time you are reading this, cracked open and flimsy, I will have birthed again. I am no closer to understanding who takes possession of this process, or locating the words to make it known.” Here we find the true function and fate of the birth story: like “My Birth,” a soft, insubstantial book held together with a bit of glue and string, each birth story has the potential to crack open, to deconstellate over time. Its elements may be preserved piecemeal by those who it touched, moving through their lives and perhaps the lives of their children and perhaps the lives of their children’s children. One day, some of those elements may be taped to a different wall in a different place, telling a different story that is still somehow the same.